Benny Villanova has seen things.

He is a Sicilian immigrant, a Vietnam veteran, a former sanitation worker, and most recently a "certified" garbologist. Benny scours the neighborhood, collecting what others throw away, then selling these treasures from his storefront garage. He and his friends like to hang out there, shooting the breeze and smoking marijuana.

Benny's charismatic, irreverent, and sometimes really funny.

He is also at war with his family. Here is a man sharing a house with his wife but living as a stranger. This is a household on the edge.

"Benny [is] a good person in one sense," says a friend and neighbor. "In another sense, he's crazy."

For an account of the challenges faced by the workshop team, see the accompanying essay Unanswered Questions.

The American-Made Benny is a product of the MediaStorm Storytelling Workshop, where participants work alongside MediaStorm staff to create an intimate, character-driven documentary in just one week. Learn more about upcoming MediaStorm workshops and online training at mediastorm.com/train.

The American-Made Benny: Benny watches in split screen - MediaStorm Storytelling Workshop

Benny is a “certified” garbologist. He collects what others throw away. Benny is also at war with his family. Here is a man sharing a house with his wife but living as a stranger. This is a household on the edge.

Credits

Special Thanks

to those who contributed their thoughts and provided feedback (alphabetically): Shameel Arafin, Lisa Jamhoury, Joe Fuller, Bill Johnson, Tim McLaughlin, Brian Storm, Marcin Szczepanski, and Ellen Tarlin

Testimonials

Marcin Szczepanski, Video and Photography

I have admired MediaStorm projects for many years now and I was very excited to be able to attend the Advanced Storytelling Workshop this year.

In many ways, the experience started several weeks before we arrived to Brooklyn. My team members and I spent quite a few nights searching for the best potential stories, subjects and issues. We contacted potential subjects directly, discussed with other team members what's doable and what aspects of the potential stories are the most promising. It was a fascinating experience that set this workshop apart from others.

During the workshop I had a chance to listen to Brian Storm discuss in detail the making of several amazing projects produced by MediaStorm. I also had a chance to learn from, and work with Rob Finch, one of the best shooters I know. His thoughtful approach to storytelling, attention to detail, and eye for meaningful images was truly inspiring. Finally, I had a rare opportunity to get inside of the head of a great video editor Eric Maierson and spend hours watching his editing decisions. Eric's relentless pursuit of best editing strategies in an effort to convey the emotions and twists of the story was very instructional.

The workshop gave me a unique opportunity to learn from some of the best people in the industry while spending a week in New York City. The effort and amount of time MediaStorm producers put into creating a great story is truly inspiring.

Markel Redondo, Video and Photography

I have been looking at MediaStorm for a long time and been able to see how it actually functions from the inside, choosing the right story, preparing interviews, recording sound and working with a team has been of a great value to me. The first training day was very useful in order to take into account all the aspects that make a good story. We had a challenging story with some frustrating moments but I think that was part of the experience and I have learnt a lot from that too. As a photographer I am used to work on my own and seeing how MediaStorm works has proven me that working together is always successful.

Bill Johnson, Video, Photography and Editor

The MediaStorm Storytelling Workshop came highly recommended and exceeded my expectations. The team from MediaStorm included Eric Maierson, Rob Finch, and Leandro Badalotti under the guidance of Brian Storm. It was clear from the start that all involved had a tireless passion for story telling and worked extremely hard to tell the best story possible.

The effort started upon being selected for the workshop with the push to find a compelling person to interview. I learned a lot about researching stories, who makes a good candidate, tracking down contact information, and enjoyed cold calling to help line up the story. We set a new record for pre-workshop emails as my teammates Marcin Szczepanski and Markel Redondo, along with Eric and Rob, dug in to research and debate story ideas.

The first day of the workshop was Brian going over his approach to story telling, the structure of the week, and a detailed review of past workshop videos to get an understanding of what makes a great story work. It was clear that our objective was to tell the person’s story to the best of our ability. The video we were to produce was a gift to the person being interviewed and brought the responsibility of getting the story right.

Rob led the effort in the field, and did a superb job of explaining the technical side of setting up shots. Rob was diplomatic and persistent in getting the subject of our video, Benny Villanova, to allow us personal access into his daily routine.

Eric led the effort of editing and constantly bounced ideas off others to get feedback. Brian focused on the narrative and provided guidance on which sections were most meaningful and the sequence of the story.

Leandro was a workhorse editing hours and hours of B-roll shots, researching music clips, and maintaining back up copies throughout each step of the process.

The strength of the MediaStorm approach is the use of dual tracks -- written narrative and video editing – to hone in on the story line. The written narrative or dialog set the primary arc of the story based on a formal interview with Benny. The written narrative was edited down to a tight sequence of plot points, and illustrated in Adobe Premier Pro by the layering in of B-roll shots taken by Marchin, Markel and Rob.

As a workshop participant in the editor role, I watched Eric’s approach to editing that can only be described as a blizzard of subtle adjustments to audio and video tracks. The edit in and out points were constantly refined and checked with the written narrative. I found it particularly insightful to see how Eric overlapped transition points and adjusted changes in volume to good effect.

There were two teams working on different stories during the week. The final event of the workshop was the screening of both stories. It was helpful to see the differences in the way the teams shot their stories and to discuss the challenges both faced in getting to the personal motives of their subjects. There was healthy debate about whether or not we got the story right and the ethics of showing the result to the world.

Just as the one-week workshop was preceded by a month of preparation, I am finding that reviewing the pages and pages of notes made during the week is a continuing learning tool.

Most importantly, I enjoyed my time immersed in the family of passionate storytellers that is MediaStorm. It was like drinking from a fire hose, and I will be reliving the experience again and again to gain a better insight into dramatic storytelling.

Thank you Brian and the rest of the MediaStorm team!

Related Links

Essay

The Challenge of The American-Made Benny

We had numerous challenges in reporting, producing, and in making the decision to ultimately publish this story. We feel this story is incomplete due to access issues and time constraints inherent with MediaStorm's approach to a workshop story. Sometimes you can learn as much from your shortcomings as from your successes. As such, we hope this will serve as an important case study about the ethics of storytelling.

- Brian Storm, MediaStorm

Unanswered Questions: On the Limits of the Single-Subject Interview by Eric Maierson

By any measure, the MediaStorm Storytelling Workshop is an intense week. It is a product-focused experience, meaning that unlike in other teaching environments we are wholly focused on producing the most compelling story possible, one that demonstrates the collective skills of the participants and the MediaStorm staff. The week consists of one day of lectures, three days in the field, and another three days editing. Workshop alum will tell you, it is rigorous.

Because time is so tight, the vast majority of workshop stories consist of just one interview. For 25 projects, this model served us well.

Then came Benny Villanova.

On paper it sounded perfect: a former sanitation worker who now sells other people's garbage out of his garage. The work of other reporters was also encouraging. Benny was charismatic, emotional, and a bit over-the-top. These were all good signs. From four years of experience, we've learned that workshop stories that occur in a primary location and involve repetitive events, like selling garbage, often succeed. They help eliminate variables so that students can focus on storytelling and technique.

But as is so often the case, the reality was full of surprises. Rob Finch, my counterpart who led the workshop participants in the field, describes his experience:

"Benny met the crew at 10:00 on a Sunday morning with four beers in hand. He told us to wait there with our drinks, he had to go change clothes, he had just "shit his pants." He came back out with a bag of pot and asked if we smoked.

It was clear that we had walked into a somewhat more complicated situation than anticipated.

I have never been in a situation like this with a source. Just getting him to focus on sitting down for an interview was challenging, and once it started, I could not rein him in. We've all been in difficult interviews, but this was different. Even when we told him we needed to reset our cameras, change cards, etc., he would not stop talking. He would scream at us, "I'm not stopping!" and just keep going. He'd cry, yell, jump out of his seat. It was like he was vomiting his story. It was an explosion, and we were trying to do triage.

His family was essentially hiding from us, and he was continually putting them down. He'd either scream at them from the other room or tell us disparaging stories about them. He was ruthless. We knew we needed to understand what was going on. He could not adequately explain himself in the short window we had, so who could help?

The only people who could give us that perspective were his family. Was this just Benny's act? Was there something else going on? Off camera, I tried over and over to get them to talk. At the beginning, it seemed like they were genuinely mad at us for being there. In retrospect, I have no doubt that Benny never talked to them about this story or asked if it was OK if we came over

I spent a few hours sitting in their dining room trying to get more information. It was clear they were concerned about the project. They told me about drugs, alcohol, mental illness, verbal abuse, and a general meanness.

Benny's daughter told me how difficult it was having us there, how much they did not like attention paid to Benny. She said people did not see the real Benny. They saw the funny but charming guy written about by The New York Times.

She was right; that was the Benny we originally thought we'd be interviewing.

I tried to explain that without their voices, this was going to happen again. But, in the end, I could not get them to discuss it or be on camera at all. I don't know if it was actual fear or just a desire to avoid attention, but it was clear that after three days of trying, I was out of luck."

AN UNRELIABLE NARRATOR

So in the end, we were left primarily with Benny's point of view. Granted, by necessity most of our workshop pieces contain just one interview, but this story is different. This is, in part, because Benny makes substantial accusations about his family that they chose not to address. That is their right, of course. But the result is a lesser, more inconclusive story. One that makes it harder to understand Benny's complex relationship with them.

The short interview with Benny's neighbor Kevin Darnell helps somewhat in this regard. He voices the strongest challenge to Benny's narrative. He refers to Benny as "crazy" and seems at times baffled by his behavior. Still, Kevin's reluctance to really speak his mind is, I think, obvious. Why did he break down during his interview? What exactly was so upsetting? Like so much else in this project, these questions are unresolved.

More to the point, the problem with relying so heavily on Benny's interview is that he is, I believe, an unreliable narrator. Quite honestly, I'm still not sure what parts of his story are accurate (Vietnam), which are exaggerations (his version of married life), and what might be sheer fabrication (why he was fired from the Sanitation Department).

We know that Benny has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder by the Veterans Administration. The team in the field saw his medical card. There were also intimations from Benny's daughter that he had been diagnosed with some form of mental illness, but no further details were provided.

We remain unclear, though, about the circumstances of his departure from the Sanitation Department. Benny says he was fired for allegedly taking money. A neighbor, who wanted to remain anonymous, told Rob that Benny was caught stealing from construction sites.

Further, we're unlikely to know what exactly transpired in the fight between Benny's son and daughter. Did Benny break up the fight as he describes, or was he actually involved? The combination of limited time and only one version of the story precludes a definitive answer.

Benny told us that if we searched his criminal record there would be no history of physical abuse. So we did that. MediaStorm hired a private investigator, and just as Benny had assured us, there was no such record. Yet this fact is also inconclusive.

Benny himself describes physical altercations with his family. In one interview, he details an occasion when his wife allegedly hit him several times. Did the violence go only one way? We can make assumptions about the nature of their relationship, but the fact remains, with only Benny explaining his side of the story, we simply don't know.

As the producer, the person who put this story together, I struggled with these uncertainties constantly. Everyone involved did. If we told only Benny's version, would it be deceptive or was I undervaluing the viewer's capacity to analyze Benny's character? What is the solid ground for the viewer to stand on from which to answer these questions? In other words, did I provide enough clues to allow someone to make informed decisions, or did I simply say, "Here's what Benny says; you figure it out." I worry it's the latter.

THE GOOD AND THE HARM

At MediaStorm, we ask what is the good and what is the harm that can come from a story. Many on our staff questioned the effect this piece would have on Benny's relationship with his family. Would it help to somehow heal their relationship, or, more dramatically, could it be a catalyst for turmoil and possibly violence in their household?

I don't think any of us knows Benny or his family well enough to predict. The workshop participants spent three days with Benny. In many ways, that's a luxury when compared with the time many in our industry are afforded. Frankly though, I think spending more time with Benny would be the only way to improve our understanding of him—which is not a criticism of anyone involved but the reality of trying to understand such a complicated person in just three days.

Consider the major issues Benny discusses: immigration, Vietnam, PTSD, drug use, cancer, financial hardship, and the list goes on. In reality, a team of journalists could spend a year excavating Benny's story. In three days, we've simply opened the front door.

NECESSARY COMPROMISES

The larger issue, I suppose, is what is our primary responsibility as storytellers? Is it to tell the story or to the potential safety of our subjects?

I am a storyteller, so I believe that our obligation lies in telling a story that is both factually accurate and emotionally honest. That should be our ideal. But I also recoil at the idea of inflicting pain on others. Life is filled with necessary compromises and, sometimes, I believe it's necessary to adapt our work accordingly.

In short, I don't think there is a definitive, always correct answer to the question of where our responsibility lies. We can never know just how far the ripples of our actions will reach nor can we sit in paralysis, always questioning the unanswerable implications of our work.

To be blunt, when debating whether this project should be published or not, I have to admit that for a long time I was not thrilled by either option. In fact, I'm still unsettled.

But I am, however, confident in our intentions.

I know that despite the many frustrations and limitations of the project, everyone involved devoted their skills to portraying Benny as accurately as our collective talents allowed, including an additional three weeks of post-production once the workshop concluded. The entire MediaStorm staff (and many non-staff, too) engaged in numerous screenings and lengthy discussions about this project and its implication.

Prior to publication, in fact, we screened the piece for Benny at his home. Because the subject matter of this project was both highly personal and deeply complex, we wanted an opportunity to gauge our accuracy. Were we being accurate? Were we being fair? You can see Benny's response in the accompanying video,

Epilogue: BennyResponds. (Subsequent to Benny's viewing, we made several small tweaks to the piece based on a prior screening. No changes were made in response on Benny's feedback.)

We also made plans with Benny's wife, Maria, to watch the project without her husband and without cameras. While she agreed to this over the phone, and even seemed eager, Maria left the house while we were still interviewing her husband. We left a follow-up phone message, but our call was not returned.

Finally, for additional insight, we spoke with a PTSD counselor at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. While she was careful not to diagnose Benny from a distance, she did say that "bizarre" behavior does not necessarily correlate with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and that "if" Benny did in fact have PTSD, he most likely suffered from other psychiatric issues as well.

The expert made it clear that many veterans, including those who served in Vietnam, cope quite well, even with PTSD. They live fulfilling lives in every strata of society.

In the end, I think Benny should be seen because of the larger issues that deserve our collective attention. Perhaps most glaringly is the question of how reliant should we be on a single interview to tell a story. This technique seems to be a mainstay not just in workshops but in much of multimedia. Too frequently, I think many of us have been guilty of taking our subject's word at face value and then using b-roll to illustrate their point of view, all without much critical analysis.

On the one hand, I do not want to produce the multimedia equivalent of dictation. On the other, I believe objectivity is a fallacy, that if we start down the road of "correcting" everything a person says, we'll end up with an unwatchable version of he said/she said. There has to be a balance, and, for every project, the measurement of that balance will be different.

But without a counterpoint here, I maintain that Benny is a deeply flawed but endlessly fascinating piece of work.

Much like the man himself.

-

Eric Maierson

December 2012

Press

The MediaStorm One Day Master Class provides a general, yet precise, overview of documentary video and multimedia storytelling approaches. MediaStorm founder Brian Storm will walk you through specific examples as well as proven tips to improve your interviewing, editing and distribution techniques.

These are the upcoming one day workshop dates:

The MediaStorm Methodology Master Class gives participants a chance to look inside the workings of a successful film and interactive production company, while taking them step-by-step through both the creative and business aspects of digital storytelling.

Founder Brian Storm will share MediaStorm’s workflow and storytelling methods and discuss essential elements of project organization and storytelling concepts.

You can attend the workshop in Los Gatos, CA in person or online via Zoom.

Upcoming date:

- December 12 - 14, 2025 - (Deadline to apply is Nov 1)

MediaStorm Storytelling Workshop Stories

A family is determined to give their disabled son a whole and vital life. In the midst of a great burden, one small child – with a seemingly endless supply of love – is the blessing that holds a family together.

Virginia Gandee's brilliant red hair and dozen tattoos belie the reality of this 22-year-old's life. Inside her family's Staten Island trailer her caregiving goes far beyond the love she has for her daughter.

For Walter Backerman, seltzer is more than a drink. It’s the embodiment of his family. As a third generation seltzer man, he follows the same route as his grandfather. But after 90 years of business, Walter may be the last seltzer man.

Using humor and a love of fantasy, "The Amazing Amy" Harlib connects with audiences through performing strenuous yoga-based contortion acts in New York City.

Benny is a “certified” garbologist. He collects what others throw away. Benny is also at war with his family. Here is a man sharing a house with his wife but living as a stranger. This is a household on the edge.

Jay Singer has been in love with one Brooklyn neighborhood his entire life. He grew up there, pined for it when he was forced to leave and returned when he couldn’t stand to be away. “Coney Island Jay” really loves Coney Island.

Tim Obert has been a commercial fisherman since he was 12. But regulations aimed at saving whales and salmon in California leave him struggling to find balance between his dream, his family’s needs and the industry he loves.

Kryssy Kocktail grew up in troubled family and, as an adult, followed the mythic path of joining the circus. Amid the lights and energy of the Coney Island Circus Sideshow, she has found something that she never dreamed would be hers.

One evening, David Sheets read a story about a new basketball arena proposed for his neighborhood. Then he realized the plans were drawn right over his house. Hold Out is the story of a few neighbors who haven't been very easily dislodged.

Joe Soll has spent half of his life searching for his birth parents, in the process he uncovered a mystery that’s haunted him for years.

Diana Ortiz spent over half her life in prison for a crime she committed when she was a teenager. Now 45, she has turned her life around and works to help other inmates rebuild their lives. Exodus is her story.

Additional Training Products

MediaStorm's award-winning team of producers and cinematographers lead online training videos with lessons learned from their experience producing films and training groups and organizations around the world.

Developed over seven years and more than 100 projects, our downloadable post-production workflow covers every phase of editing, from organizing assets through outputting final projects and archiving.

Available for iPad on iTunes, the MediaStorm Field Guide outlines fundamental concepts for gathering multimedia content in the field for documentary films.

MediaStorm Project Showcase

Once teetering on the brink of extinction, the Santa Catalina Island Fox made a dramatic recovery. Its resurgence marks one of the greatest conservation success stories in United States history.

In the shadow of Silicon Valley’s booming technology industry, a growing number of people remain out in the cold. Skyrocketing housing prices in America’s hub of innovation have pushed many onto the streets, straining policymakers to find solutions to a homelessness problem that impacts everyone in the community.

This page recognizing Zora J Murff for ICP’s 2023 Infinity Award for Documentary Practice and Visual Journalism features a film about his life, a slideshow of his projects and extra clips of his thoughts about his work and motivation.

Sebastião Salgado says "a good picture, a fantastic picture, you do in a fraction of a second, but to arrive to do this picture, you must put your life in there."

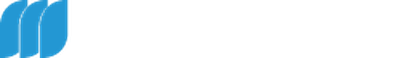

Esther Horvath has sent questions to the universe and she has received answers. She found her calling to tell visual stories that show the full research story behind our climate data.

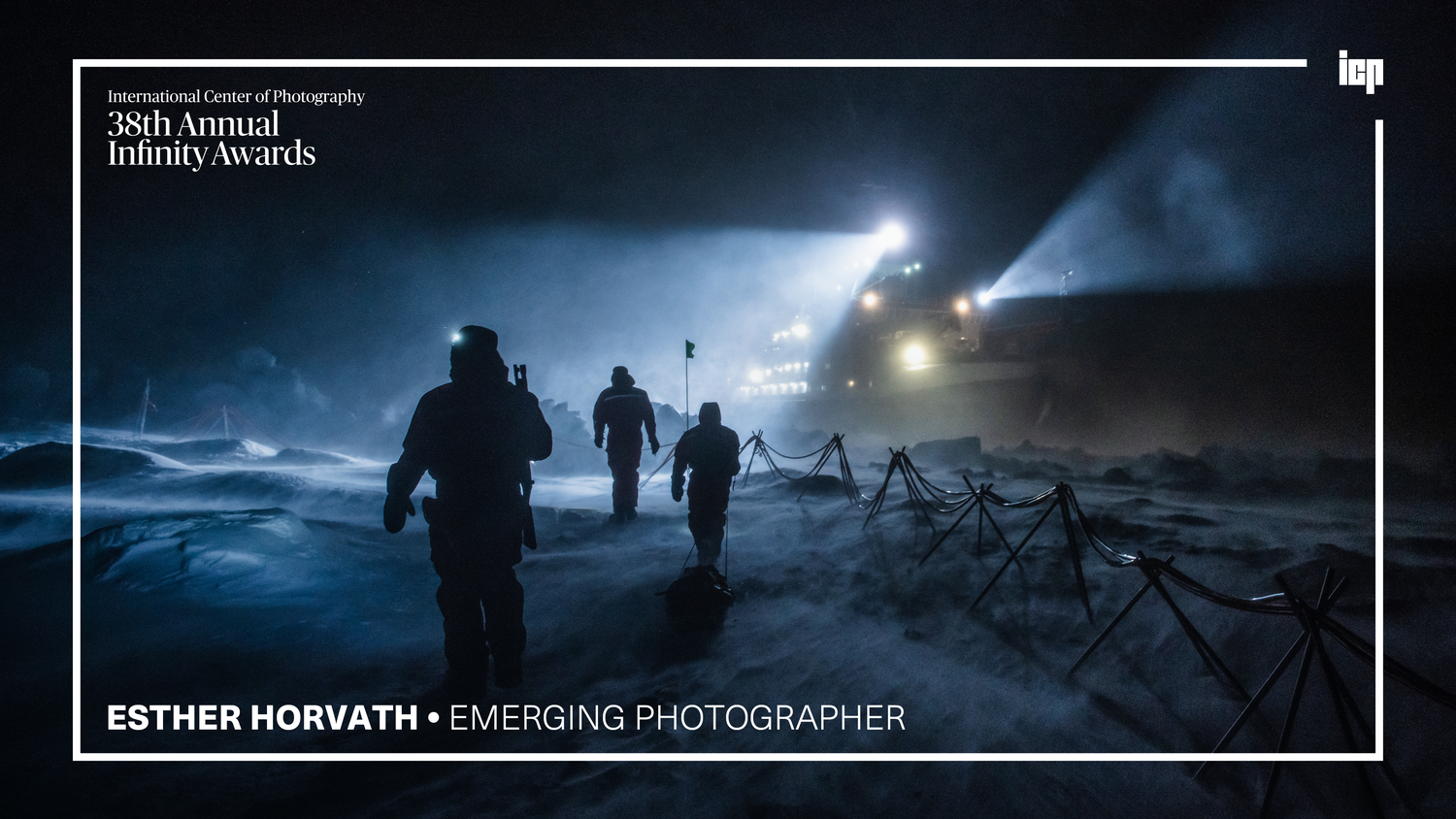

See photographer Acacia Johnson’s growth from her earliest explorations of Alaskan landscapes to a National Geographic cover for a documentary project among indigenous people of the Arctic.

Sir Don McCullin never intended to become a photographer. He found it hard to believe he’d ever escape the poverty of North London. But a spur of the moment photograph launched McCullin into a career spanning 50 years in photography.

As the U.S. prepares for the final drawdown of soldiers from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, Soledad O’Brien and MediaStorm take an intimate look at two veterans as they struggle with the transition from war to home.

Writer Zadie Smith pays homage to photographer Deana Lawson in the artist’s first Monograph for Aperture.

As a formerly incarcerated person, Michael struggled for work, and found purpose in being a husband, father, and activist. But 7 years since his release from prison, the cost of Michael’s activism is evident.

Benny is a “certified” garbologist. He collects what others throw away. Benny is also at war with his family. Here is a man sharing a house with his wife but living as a stranger. This is a household on the edge.

Photographer Amber Bracken recognized something deeper than a protest was afoot when hundreds of tribes gathered at the Standing Rock reservation in opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline.

How does the death of a child change a parent? How does the death of a parent change a child? How do these moments change us as we develop and grow further away from who we were as children?

Maurice Berger–cultural historian, and columnist for the New York Times’ Race Stories–has spent his career studying and teaching racial literacy through visual literacy.

Japan’s Disposable Workers examines the country’s employment crisis: from suicide caused by overworking, to temporary workers forced by economics to live in internet cafes, and the elderly who wander a town in search of shelter and food.

Karl Ove Knausgaard is the celebrated author of a massive six-volume autobiography. But Knausgaard remains confused by the attention. This is a portrait of a man who has achieved massive success yet still considers himself unworthy.

Michael Thomasson has devoted his life to video games. It’s been his passion and his obsession for more than three decades. He owns over 11,000 unique game titles for more than 100 different systems.

A film about Michael Christopher Brown for the 2017 ICP Infinity Awards.

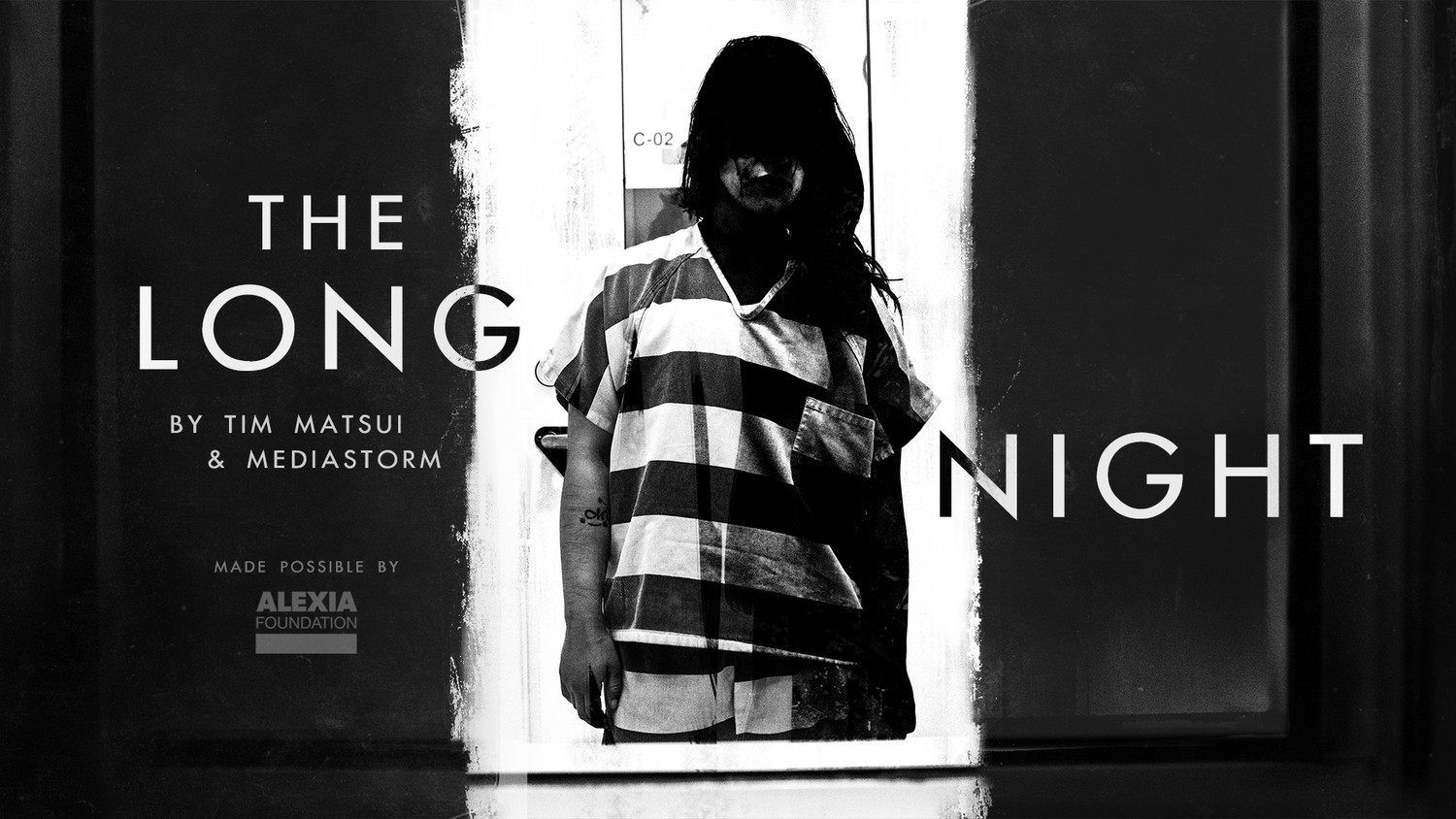

The Long Night, a feature film by Tim Matsui and MediaStorm, gives voice and meaning to the crisis of minors who are forced and coerced into the American sex trade.

Jonathan Harris and Greg Hochmuth have a complicated relationship with the internet and have worked together to develop an artwork that explored some of the more difficult consequences of what it means to live with the internet.

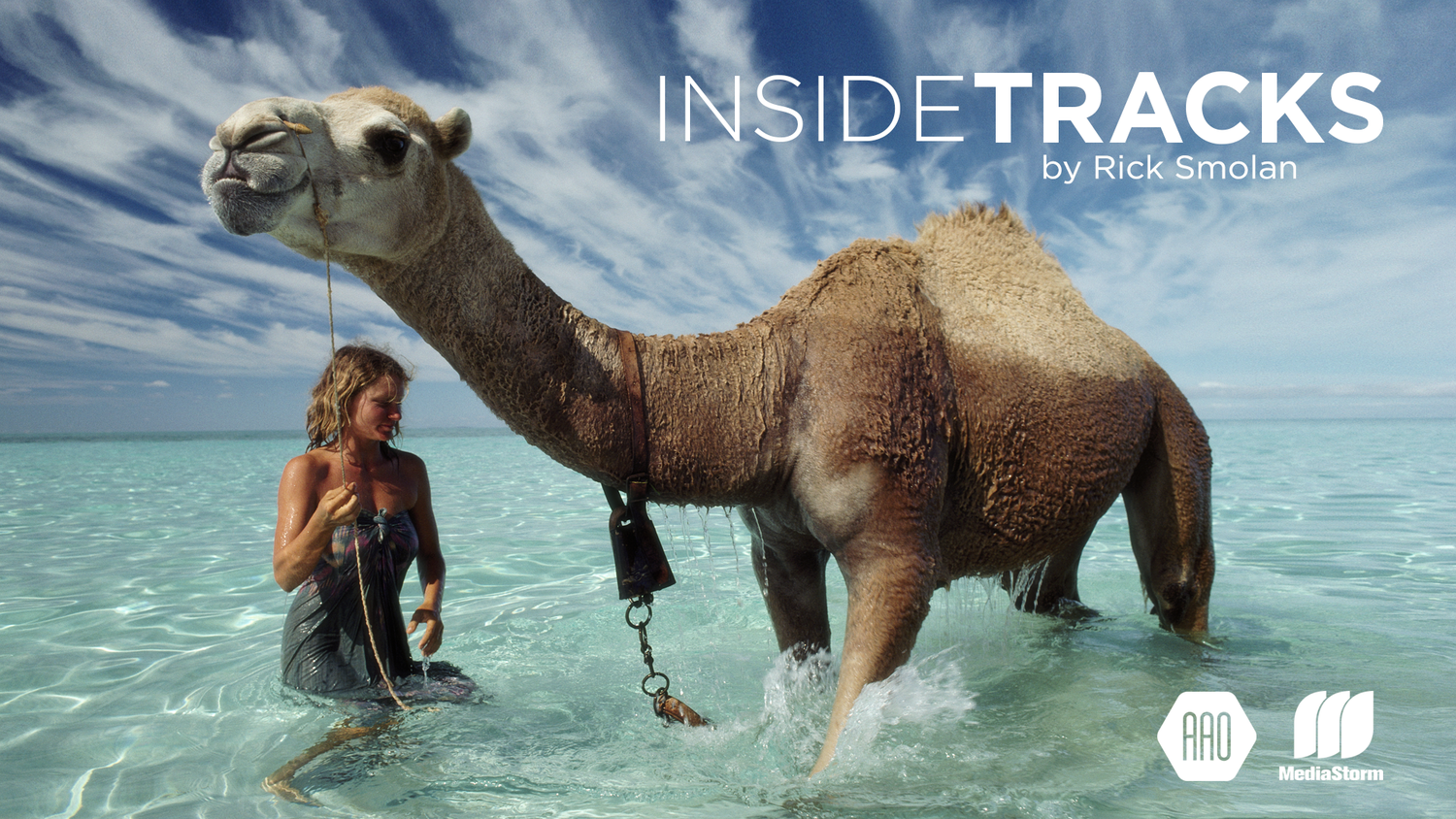

In 1977, Robyn Davidson walked 1,700 miles across the Australian outback. National Geographic sent Rick Smolan to photograph her perilous journey—a trek that tested and transformed them, forming an immutable bond that continues to this day.

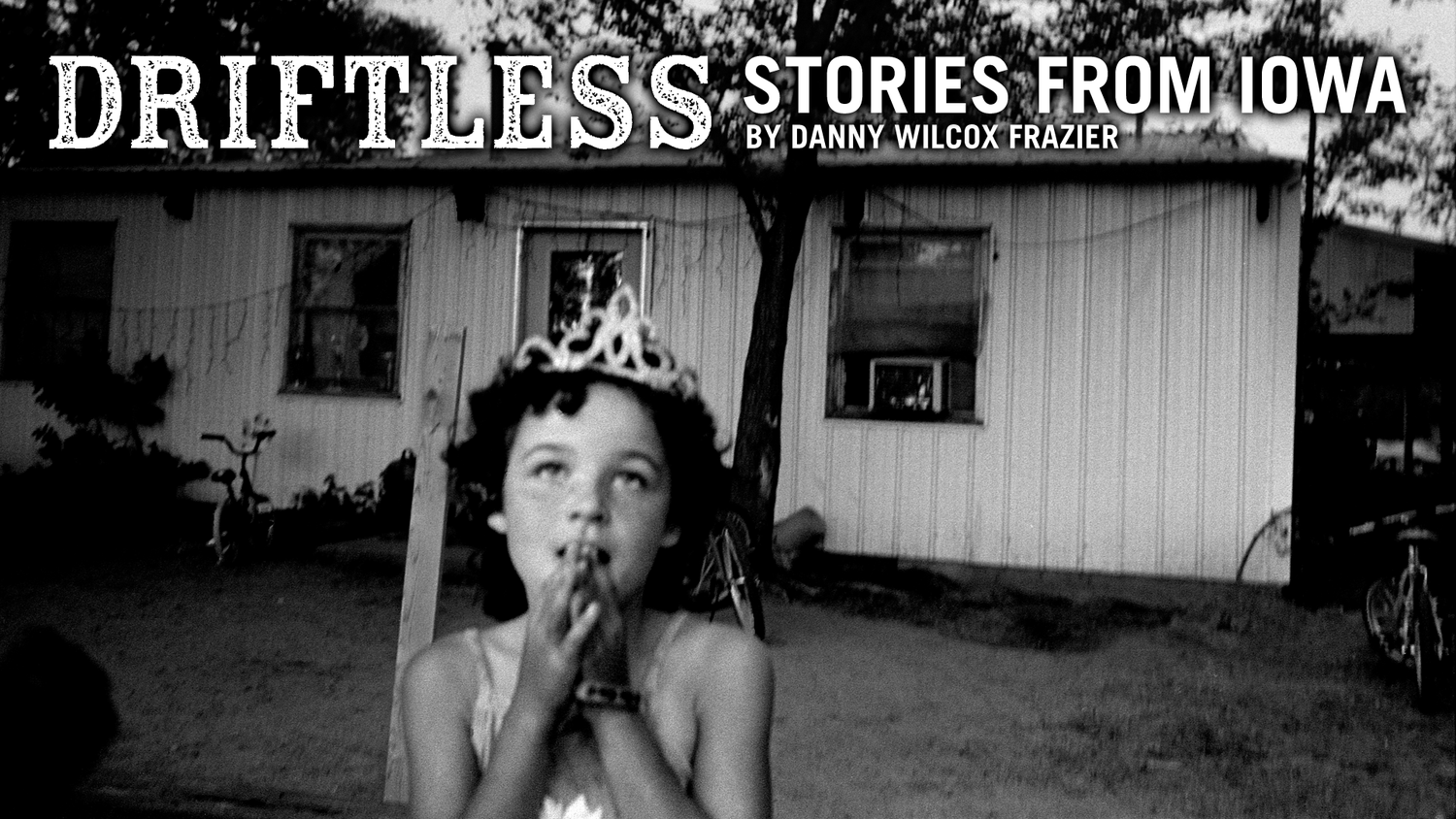

Once at the center of the U.S. economy, the family farm now drifts at its edges. In Iowa, old-time farmers try to hang on to their way of life, while their young push out to find their futures elsewhere. Driftless tells their stories.

The American family farm gives way to a subdivision - a critical cultural shift across the U.S. Common Ground is a 27-year document of this transition, through the Cagwins and the Grabenhofers, two families who love the same plot of land.

For Walter Backerman, seltzer is more than a drink. It’s the embodiment of his family. As a third generation seltzer man, he follows the same route as his grandfather. But after 90 years of business, Walter may be the last seltzer man.

Larry Fink has spent over 40 years photographing jazz musicians, wealthy manhattanites, his neighbors, fashion models, and the celebrity elite. His archive is a thoughtful collection of American history, and Fink’s experience of it.

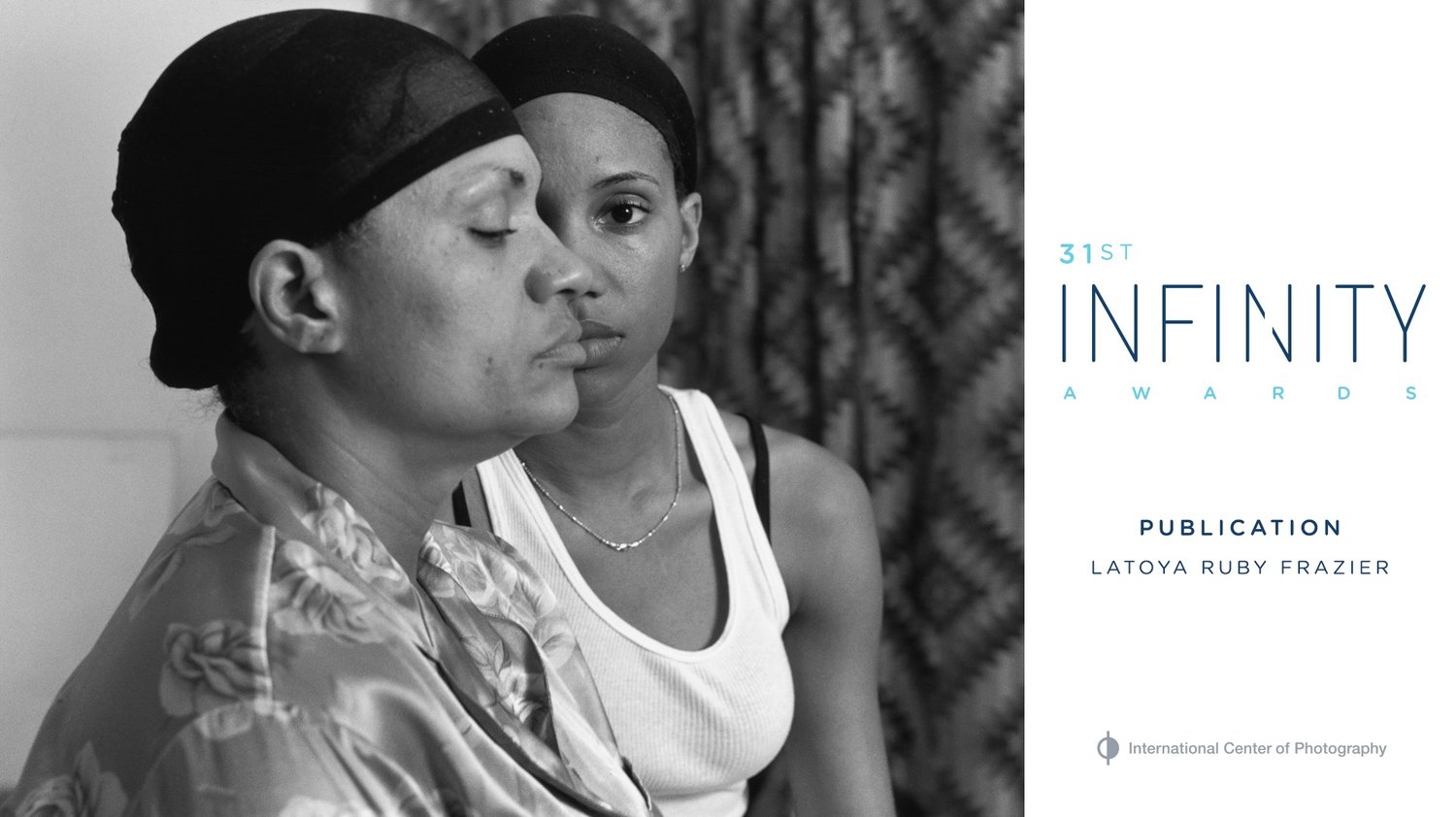

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s body of work “The Notion of Family” examines the impact of the steel industry and the health care system on the community and her family. Collaborating with her mother and grandmother, she uses her family as a lens to view the past, present and future of the town.

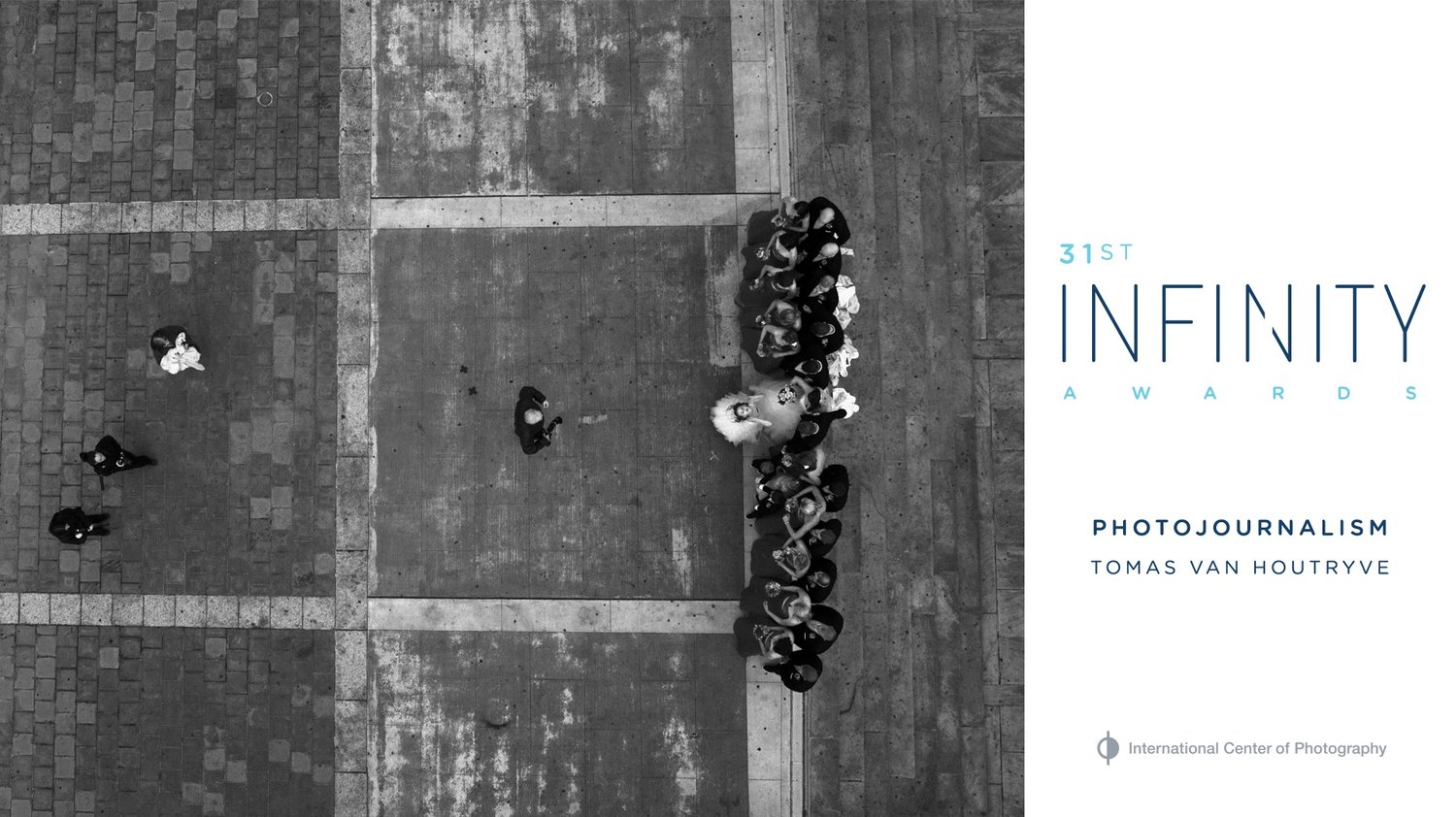

Tomas Van Houtryve wants there to be a permanent visual record of the dawn of the drone age, the period in American history when America started outsourcing their military to flying robots. In order to create this record, Van Houtryve sent his own drone into American skies.

Evgenia Arbugaeva was born in the magical town of Tiksi, Russia. This barren, arctic landscape influenced Arbugaeva in almost every aspect of her dreamlike photography.

Surviving the Peace: Laos takes an intimate look at the impact of unexploded bombs left over from the Vietnam war in Laos and profiles the dangerous, yet life saving work, that MAG has undertaken in the country.

A family is determined to give their disabled son a whole and vital life. In the midst of a great burden, one small child – with a seemingly endless supply of love – is the blessing that holds a family together.

Inspired by the photographs of the Farm Security Administration growing up, Lynn Johnson has spent nearly 35 years as a photojournalist working for LIFE, National Geographic, Sports Illustrated and various foundations.

Resetting the Table takes a unique, personal look at the impact Starbucks’ Create Jobs for USA program has had on the American Mug & Stein pottery facility in East Liverpool, Ohio.

Hungry Horse captures the spirit of renewal, peace and serenity through stunning landscapes and intimate oral histories.

Using humor and a love of fantasy, "The Amazing Amy" Harlib connects with audiences through performing strenuous yoga-based contortion acts in New York City.

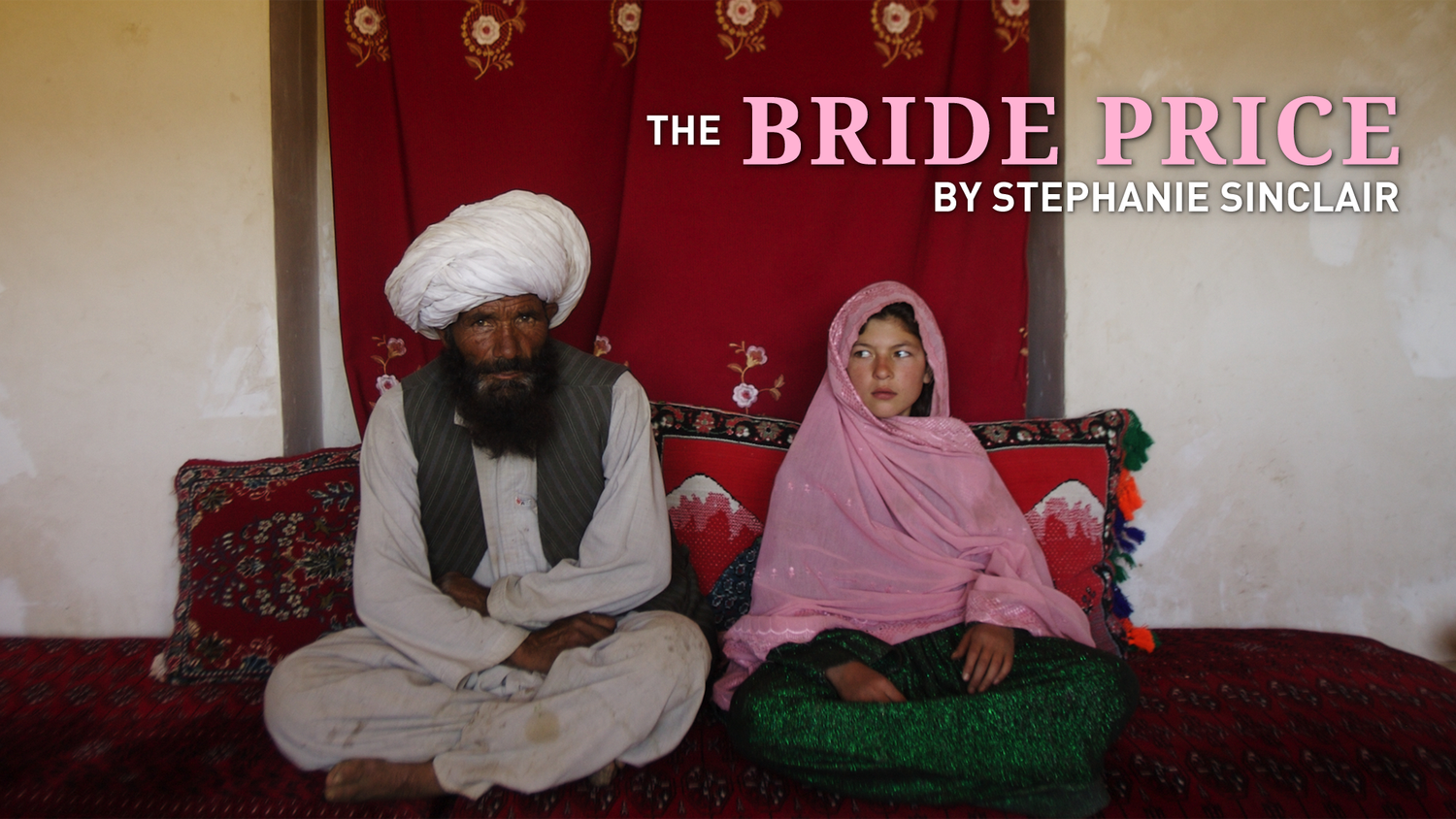

In many countries, girls as young as eight are forced into marriage by their families, culture and economic situation. This practice destroys their chance at education leading to tragic results.

Surreal and mysterious, North Korea was a black hole to outsiders wanting a glimpse of the country. That all changed in 2012, when AP photographer David Guttenfelder led the opening of the bureau's newest office inside the North Korea.

Virginia Gandee's brilliant red hair and dozen tattoos belie the reality of this 22-year-old's life. Inside her family's Staten Island trailer her caregiving goes far beyond the love she has for her daughter.

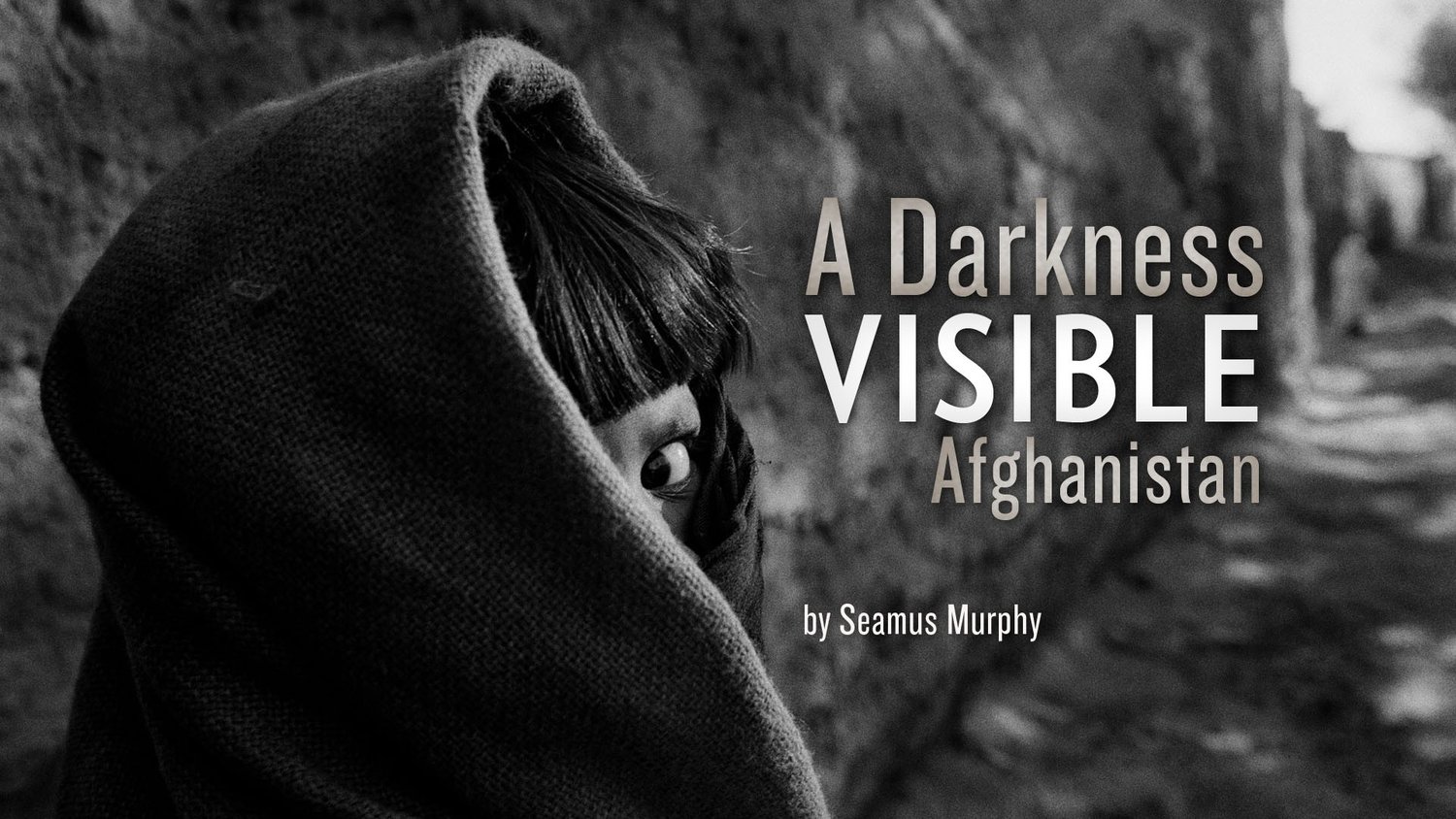

Based on 14 trips to Afghanistan between 1994 and 2010, A Darkness Visible: Afghanistan is the work of photojournalist Seamus Murphy. His work chronicles a people caught time and again in political turmoil, struggling to find their way.

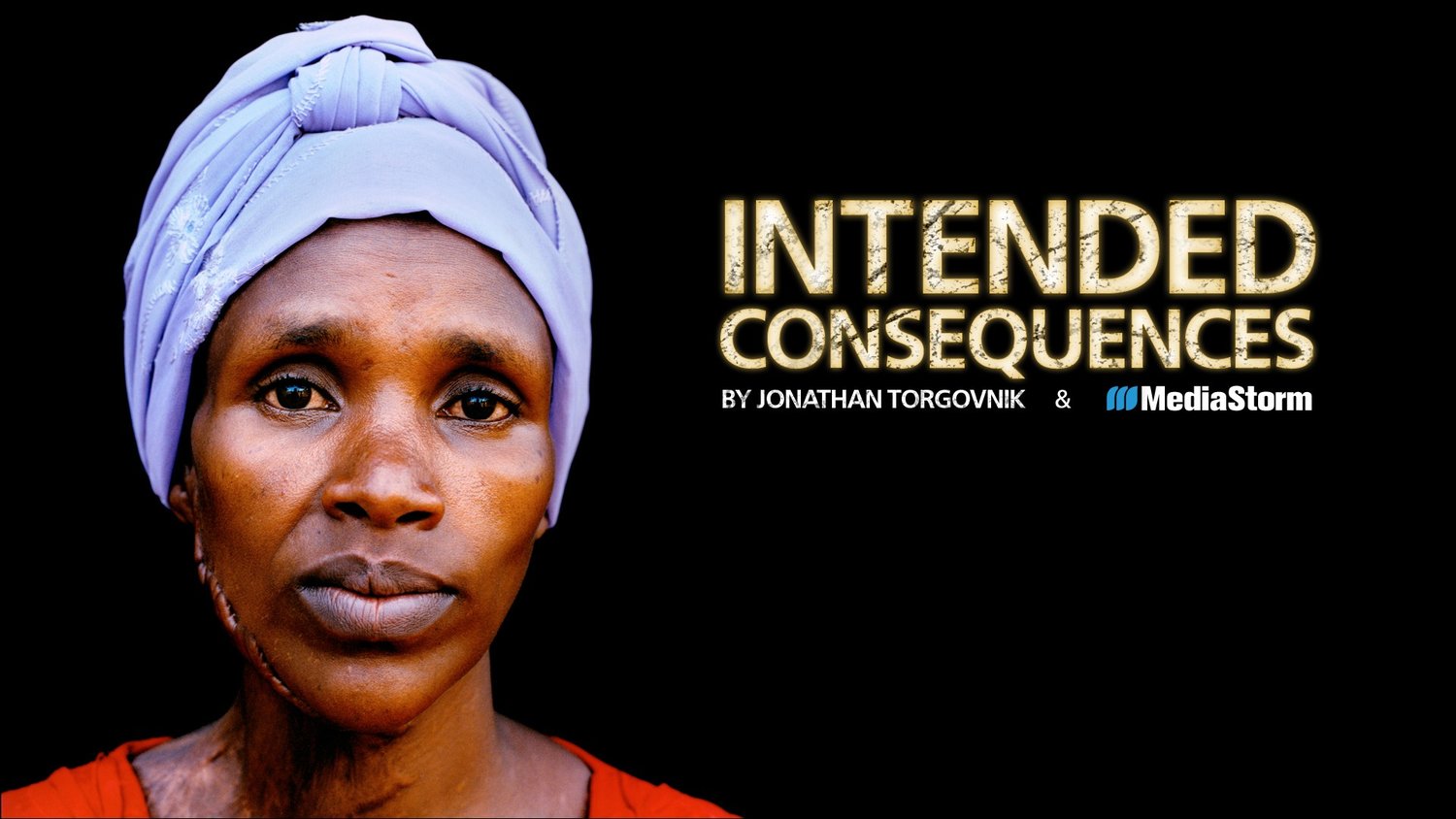

In Rwanda, in 1994, Hutu militia committed a bloody genocide, murdering one million Tutsis. Many of the Tutsi women were spared, only to be held captive and repeatedly raped. Many became pregnant. Intended Consequences tells their stories.

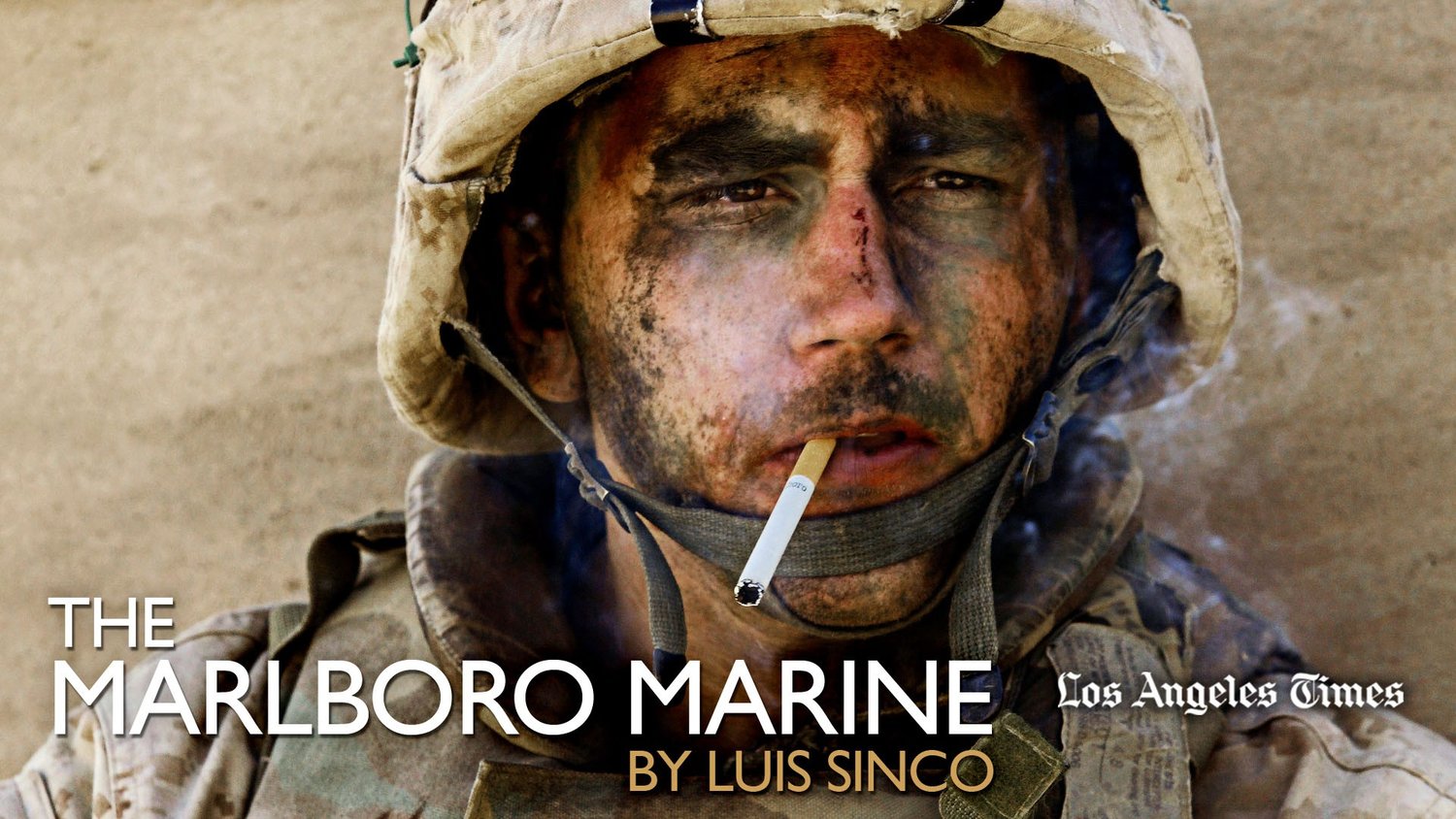

To those who serve in the armed forces, what is the aftereffect of war? The Marlboro Marine is photographer Luis Sinco's portrait of Marine Corporal James Blake Miller, whom he met in Iraq. For Miller, coming home has been its own battle.

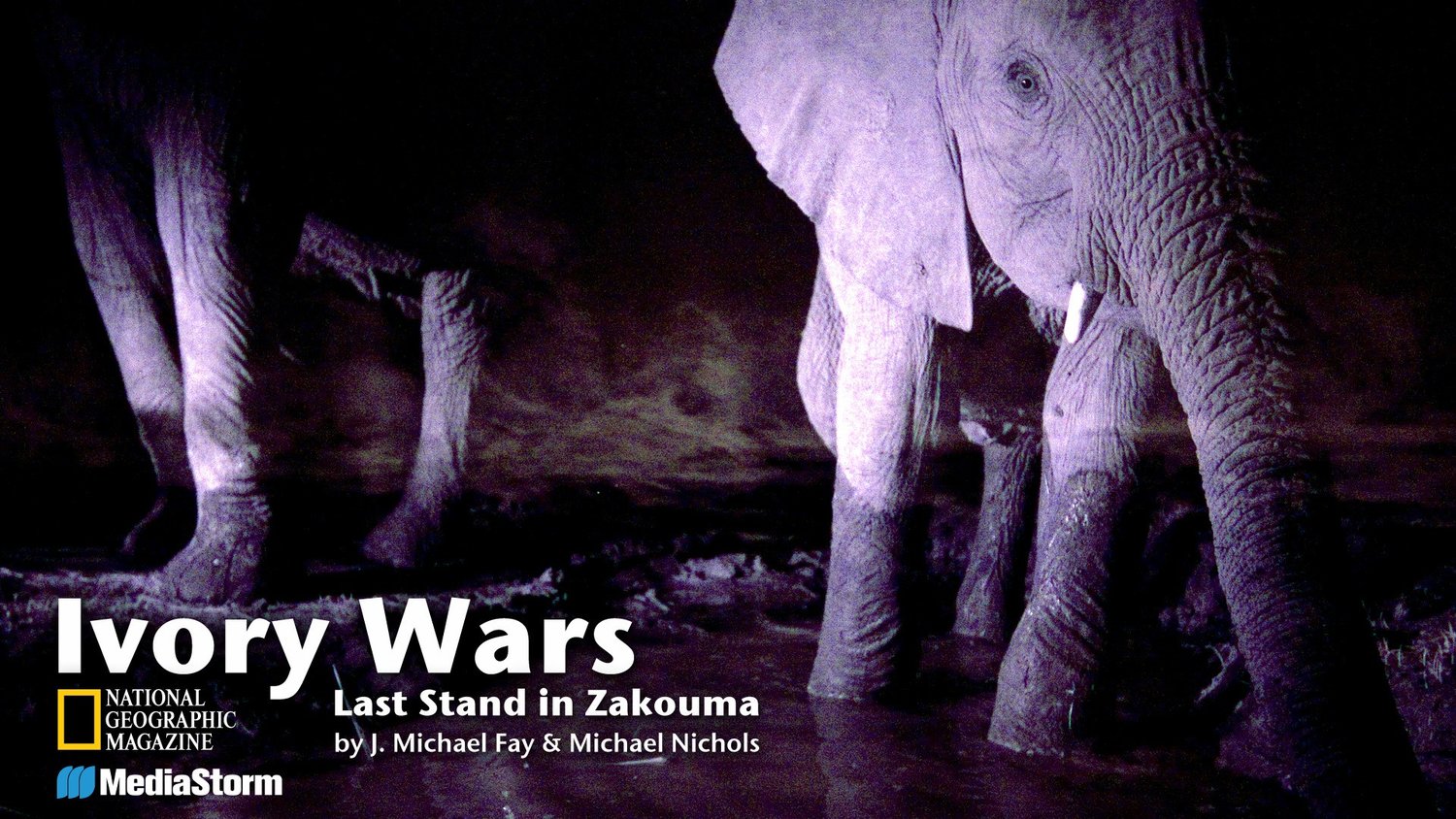

Zakouma National Park is one of the last places on earth where elephants still roam by the thousands. In a land where poachers will slaughter the huge animals for their tusks alone, it takes armed guards to keep them safe.

Kingsley's Crossing is the story of one man's dream to leave the poverty of life in Africa for the promised land of Europe. We walk in his shoes, as photojournalist Olivier Jobard accompanies Kingsley on his uncertain and perilous journey.

Collaborate With Us

The MediaStorm Platform is an advanced video platform that extends the user experience beyond linear video to include the interactive capabilities of the Internet.

The MediaStorm Platform is an advanced video platform that extends the user experience beyond linear video to include the interactive capabilities of the Internet.

Follow MediaStorm

Copyright 2025 MediaStorm, LLC | Terms & Conditions | Privacy | Contact