Other Americas

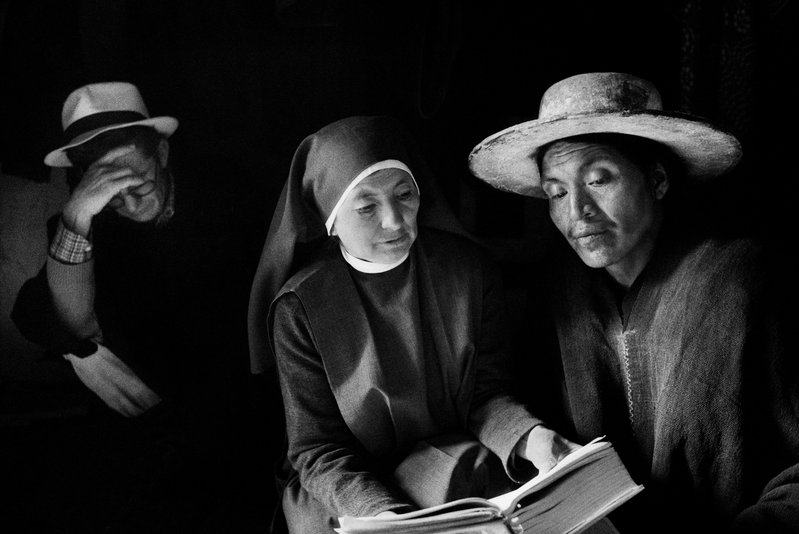

Sebastião Salgado traveled extensively in Latin America between 1977 and 1984 including Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, Guatemala and Mexico to document the shifting religious and political climate in the region.

In Other Americas, Salgado puts a human face on economic and political oppression in developing countries including portraits of farmers and indigenous people, landscapes and pictures of the region's spiritual traditions.

Related Links

Sahel

In 1984 and 1985, the region of Sahel in Africa suffered a drought at a scale that it had never reached before, while in certain countries, such as Chad and Ethiopia, war was raging on. Due to, or thanks to, the drought, the exodus was amplified and drove populations of people out from their villages to places where they could hope to survive.

In 1984 Salgado began what would be a fifteen-month project of photographing the drought-stricken Sahel region of Africa in the countries of Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and Sudan, where approximately one million people died from extreme malnutrition and related causes. Working with the humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders, Salgado documented the enormous suffering and the great dignity of the refugees. This early work became a template for his future photographic projects about other afflicted people around the world. Since then, Salgado has again and again sought to give visual voice to those millions of human beings who, because of military conflict, poverty, famine, overpopulation, pestilence, environmental degradation, and other forms of catastrophe, teeter on the edge of survival.

Related Links

Workers

From 1986 to 1992 Salgado documented manual labor around the globe resulting in a book and exhibition called Workers. This work was conceived to tell the story of an era. The images offer a visual archeology of a time that history knows as the Industrial Revolution, a time when men and women work with their hands.

More than those of any other living photographer, Sebastião Salgado's images of the world's poor stand in tribute to the human condition. His transforming photographs bestow dignity on the most isolated and neglected.

Workers is a global epic that transcends mere imagery to become an affirmation of the enduring spirit of working women and men. Covering six categories--"Agriculture," "Food," "Mining," "Industry," "Oil" and "Construction"--the book unearths layers of visual information to reveal the ceaseless human activity at the core of modern civilization.

Workers serves as an elegy for the passing of traditional methods of labor and production. Yet its ultimate message is one of endurance and hope: entire Indian families serve as construction crews to build a dam that will bring life to their land, and laborers using contemporary technology connect England and France through Eurotunnel. Honoring the timeless and indomitable spirit of the manual laborer, "Workers" renders the human condition with honesty and respect.

"Salgado unveils the pain, the beauty, and the brutality of the world of work on which everything rests," wrote Arthur Miller of this photobook classic, upon its original publication in 1993. "This is a collection of deep devotion and impressive skill." An elegy for the passing of traditional methods of labor and production, "Workers" delivers a message of endurance and hope.

Salgaod’s wife Lélia Wanick Salgado writes about this series: “The images offer a visual archeology of a time that history knows as the Industrial Revolution, a time when men and women work with their hands provided the central axis of the world.”

Related Links

Sebastião Salgado’s dramatic Workers photos – Overworked & underpaid

Sebastião Salgado’s Photojournalism Portrays the Reality of Labour Exploitation

Gold

“What is it about a dull yellow metal that drives men to abandon their homes, sell their belongings and cross a continent in order to risk life, limbs and sanity for a dream?” – Sebastião Salgado

When Salgado was finally authorized to visit Serra Pelada in September 1986, having been blocked for six years by Brazil’s military authorities, he was ill-prepared to take in the extraordinary spectacle that awaited him on this remote hilltop on the edge of the Amazon rainforest. Before him opened a vast hole, some 200 meters wide and deep, teeming with tens of thousands of barely-clothed men. Half of them carried sacks weighing up to 40 kilograms up wooden ladders, the others leaping down muddy slopes back into the cavernous maw. Their bodies and faces were the color of ochre, stained by the iron ore in the earth they had excavated.

Salgado spent weeks in a gold mine in Serra Pelada, Brazil in 1986. The Serra Pelada gold mine was active from 1980 to 1986, and currently exists as a highly polluted lake. Salgado took 28 photos of the workers and miners, capturing the expanse of horrid working conditions and suffering.

These workers made as many as 60 trips up and down the dangerous cliff, carrying heavy sacks that weighed between 30 and 60 kgs, and got paid only 60 cents for each of the trips.

The 28 photographs that Salgado took of the mine were also to be part of a larger series titled Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age 1986–921 which included 3131 photos of 42 different types of workplace scenarios from 26 other parts of the world.

After gold was discovered in one of its streams in 1979, Serra Pelada evoked the long-promised El Dorado as the world’s largest open-air gold mine, employing some 50,000 diggers in appalling conditions. Today, Brazil’s wildest gold rush is merely the stuff of legend, kept alive by a few happy memories, many pained regrets―and Sebastião Salgado’s photographs.

Color dominated the glossy pages of magazines when Salgado shot these images. Black and white was a risky path, but the Serra Pelada portfolio would mark a return to the grace of monochrome photography, following a tradition whose masters, from Edward Weston and Brassaï to Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson, had defined the early and mid-20th century.

When Salgado’s images reached The New York Times Magazine, something extraordinary happened: there was complete silence. “In my entire career at The New York Times,” recalled photo editor Peter Howe, “I never saw editors react to any set of pictures as they did to Serra Pelada.”

Today, with photography absorbed by the art world and digital manipulation, Salgado’s portfolio holds a biblical quality and projects an immediacy that makes them vividly contemporary. The mine at Serra Pelada has been long closed, yet the intense drama of the gold rush leaps out of these images.

Related Links

Kuwait

“We must remember that in the brutality of battle another such apocalypse is always just around the corner.” —Sebastião Salgado

In January and February 1991, as the United States–led coalition drove Iraqi forces out of Kuwait, Saddam Hussein’s troops retaliated with an inferno. At some 700 oil wells and an unspecified number of oil-filled low-lying areas, they ignited vast, raging fires, creating one of the worst environmental disasters in living memory.

As the desperate efforts to contain and extinguish the conflagration progressed, Sebastião Salgado traveled to Kuwait to witness the crisis firsthand. The conditions were excruciating. The heat was so vicious that Salgado’s smallest lens warped. A journalist and another photographer were killed when a slick ignited as they crossed it. Sticking close to the firefighters, Salgado braved the intense danger, stench, pollution, and scorching temperatures to capture the ravaged landscape; the air choking on charred sand and soot; the blistered remains of camels; the sand littered with cluster bombs; the flames and smoke soaring to the skies, blocking out the sunlight, dwarfing the oil-soaked firefighters.

The epic monochrome pictures first appeared in The New York Times Magazine in June 1991 and were subsequently hailed as one of the photographer’s most captivating—and courageous—bodies of work. Adding to Salgado’s roster of international accolades, the series was awarded the Oskar Barnack Award, recognizing outstanding photography on the relationship between man and the environment.

Related Links

Public Delivery: Sebastião Salgado in Kuwait & A desert on fire

Migrations

In Migrations, Salgado turns his attention to the staggering phenomenon of mass migration. Photographs taken over seven years across more than 35 countries document the epic displacement of the world's people at the close of the twentieth century. Wars, natural disasters, environmental degradation, explosive population growth and the widening gap between rich and poor have resulted in over one hundred million international migrants, a number that has doubled in a decade. This demographic change, unparalleled in human history, presents profound challenges to the notions of nation, community, and citizenship. The first extensive pictorial survey of the current global flux of humanity, Migrations follows Latin Americans entering the United States, Jews leaving the former Soviet Union, Africans traveling into Europe, Kosovars fleeing into Albania and many others. The images address suffering while revealing the dignity and courage of the subjects. With his unique vision and empathy, Salgado gives us a picture of the enormous social and political transformations now occurring in a world divided between excess and need.

Salgado’s images feature those who know where they are going and those who are simply in flight, relieved to be alive and uninjured enough to run. The faces he meets present dignity and compassion in the most bitter of circumstances, but also the many ravaged marks of violence, hatred, and greed.

Salgado also declares the commonality of the migrant situation as a shared, global experience. He summons his viewers not simply as spectators of the refugee and exile suffering, but as actors in the social, political, economic, and environmental shifts which contribute to the migratory phenomenon. As the boats bobbing up on the Greek and Italian coastline bring migration home to Europe like no mass movement since the Second World War, Exodus cries out not only for our heightened awareness but also for responsibility and engagement. In face of the scarred bodies, the hundreds of bare feet on hot tarmac, our imperative is not to look on in compassion, but, in Salgado’s own words, to temper our behaviors in a “new regimen of coexistence.”

The project had a profound impact on Salgado. He said, “The experience changed me profoundly. When I began this project, I was fairly used to working in difficult situations. I felt my political beliefs offered answers to many problems. I truly believed that humanity was evolving in a positive direction. I was unprepared for what followed. What I learned about human nature and the world we live in made me deeply apprehensive about the future.”

Related Links

Nieman Reports: Migrations: The Story of Humanity on the Move

Townsend Center Occasional Papers: Migrations

Genesis

Healing the land rekindled Salgado’s desire to photograph again. Following the trajectory of his career, we see the photographer, depleted physically and emotionally after his work on Migrations. Regeneration of land and career proceeded in tandem, except that when he focused his camera anew, this time it was not on humanity, whose future seems uncertain, but rather on the planet, which he feels confident will endure. His new project is aptly named Genesis.

What you see in his photos is an area occupying 46% of the planet, and which to this day is virgin land — the same as it was on the first day, according to Genesis. Salgado’s quest to capture nature in its original state began in 2004. During his travels across the globe, he documented arctic and desert landscapes, tropical rainforests, marine and other wildlife, and communities still living according to ancestral traditions.

Salgado wanted to go back in time, to capture those parts of the planet least touched by mankind. Genesis, the result of an epic eight-year expedition to rediscover the mountains, deserts and oceans, the animals and peoples that have so far escaped the imprint of modern society―the land and life of a still-pristine planet. “Some 46% of the planet is still as it was in the time of genesis,” Salgado reminds us. “We must preserve what exists.”

The Genesis project, along with the Salgados’ Instituto Terra, are dedicated to showing the beauty of our planet, reversing the damage done to it, and preserving it for the future.

Over 30 trips―traveled by foot, light aircraft, seagoing vessels, canoes, and even balloons, through extreme heat and cold and in sometimes dangerous conditions―Salgado created a collection of images showing us nature, animals, and indigenous peoples in breathtaking beauty.

“Genesis is a quest for the world as it was, as it was formed, as it evolved, as it existed for millennia before modern life accelerated and began distancing us from the very essence of our being,” said Lélia Wanick Salgado. “It is testimony that our planet still harbors vast and remote regions where nature reigns in silent and pristine majesty.”

What does one discover in Genesis? The animal species and volcanoes of the Galápagos; penguins, sea lions, cormorants, and whales of the Antarctic and South Atlantic; Brazilian alligators and jaguars; African lions, leopards, and elephants; the isolated Zo’é tribe deep in the Amazon jungle; the Stone Age Korowai people of West Papua; nomadic Dinka cattle farmers in Sudan; Nenet nomads and their reindeer herds in the Arctic Circle; Mentawai jungle communities on islands west of Sumatra; the icebergs of the Antarctic; the volcanoes of Central Africa and the Kamchatka Peninsula; Saharan deserts; the Negro and Juruá rivers in the Amazon; the ravines of the Grand Canyon; the glaciers of Alaska... and beyond. Having dedicated so much time, energy, and passion to the making of this work, Salgado calls Genesis “my love letter to the planet.”

“So many times I’ve photographed stories that show the degradation of the planet. I had one idea to go and photograph the factories that were polluting, and to see all the deposits of garbage. But, in the end, I thought the only way to give us an incentive, to bring hope, is to show the pictures of the pristine planet – to see the innocence. In Genesis, I followed a romantic dream to find and share a pristine world that all too often is beyond our eyes and reach.”

The Genesis project had its roots in that period of despair, Salgado said. But his faith in humanity is bigger than his doubts, and he orchestrated a volume in biblical scope.

Between 2004 and 2011, Salgado worked on Genesis, aiming at the presentation of the unblemished faces of nature and humanity. It consists of a series of photographs of landscapes and wildlife, as well as of human communities that continue to live in accordance with their ancestral traditions and cultures. This body of work is conceived as a potential path to humanity's rediscovery of itself in nature.

Genesis is his first departure from photographing exclusively humans. He wants to show the world all of the incredible, largely undiscovered and untouched nature in the world — from animals, to dense rain forests, to tribes in the Amazon. By showing the world these pictures, he hopes to encourage us to not only preserve these pristine environments, but to rebuild some of the ones we’ve already destroyed.

It is, as if he is saying: We need to save what is left, before it is too late.

“In Genesis, my camera allowed nature to speak to me. And it was my privilege to listen.” ―Sebastião Salgado

Related Links

Louisiana Channel: Sebastião Salgado Interview: Photographing the Pristine

The Guardian: Sebastião Salgado: GENESIS – review

Time: In the Beginnings: Sebastião Salgado's Genesis

Photography Office: MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY: SEBASTIAO SALGADO – GENESIS – THE LEGACY OF PLANET EARTH

YouTube: The Genesis of Sebastião Salgado

YouTube: Sebastião Salgado: Genesis | Natural History Museum

Amazonia

Sebastião Salgado traveled the Brazilian Amazon and photographed the unparalleled beauty of this extraordinary region for six years: the forest, the rivers, the mountains, the people who live there―an irreplaceable treasure of humanity. It extends over more than 2 million square miles, contains hundreds of thousands of plant and animal species and is home to the tribes of people who carry our human history within their daily lives.

In the book’s foreword Salgado writes: “For me, it is the last frontier, a mysterious universe of its own, where the immense power of nature can be felt as nowhere else on earth. Here is a forest stretching to infinity that contains one-tenth of all living plant and animal species, the world’s largest single natural laboratory.”

Salgado visited a dozen indigenous tribes that exist in small communities scattered across the largest tropical rainforest in the world. He documented the daily life of the Yanomami, the Asháninka, the Yawanawá, the Suruwahá, the Zo’é, the Kuikuro, the Waurá, the Kamayurá, the Korubo, the Marubo, the Awá, and the Macuxi―their warm family bonds, their hunting and fishing, the manner in which they prepare and share meals, their marvelous talent for painting their faces and bodies, the significance of their shamans, and their dances and rituals.

“My wish, with all my heart, with all my energy, with all the passion I possess, is that in 50 years’ time this book will not resemble a record of a lost world. Amazônia must live on.”

Related Links

The Guardian: ‘Paradise exists!’: Sebastião Salgado’s stunning voyage into Amazônia

Forbes: Salgado’s ‘Amazonia’ Seeks to Save a World

CNN: 'We must be smart enough to survive': Photographer Sebastião Salgado sees the bigger picture

YouTube: Mensaje de Sebastiao Salgado.

France 24: Sebastião Salgado's Amazonian odyssey: Sights and sounds of the forest

New Scientist: Sebastião Salgado's photographs show the beauty of Amazônia

Other Americas

Sebastião Salgado traveled extensively in Latin America between 1977 and 1984 including Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, Guatemala and Mexico to document the shifting religious and political climate in the region.

In Other Americas, Salgado puts a human face on economic and political oppression in developing countries including portraits of farmers and indigenous people, landscapes and pictures of the region's spiritual traditions.

Related Links